Achieving Research Fluency

Prepare, Submerge, Flow & Practice

“Questions were disorder awaiting organization. The more you understood, the more the world aligned. The more the chaos made sense, as all things should.”

— Rhythm of War, Brandon Sanderson

Individual research experience should ideally lead us from competency to fluency (to borrow the linguistic term). But what does it mean to be fluent in researching, and how does one reach research fluency?

Defining Research Fluency

First, we should point out two types of fluency:

Domain-specific fluency, which we can expect to be a function of personal “time-on-target” in a certain research domain.

General fluency, which can be assumed to be a function of overall personal experience in various domains of research over time, and may promote greater initial proficiency in new research ventures.

In my view, being research fluent (either domain-specific or in general) means being capable of the following:

Identifying questions in need of answers, both independently and by relying on the input of others (such as requests or dilemmas put forward by customers).

Choosing the best methods and tools for the job (as a prerequisite, we should be familiar with those available and highly competent with those most useful).

Recognizing novelty and patterns worthy of our attention (more on this later).

Efficiently searching (as in datamining, sifting and performing lookups in our raw material), “gisting” (a good guide can be found here) and curating on the go (by this I mean continuously re-organizing all our various collected reference material and notes in a sort of “Pokédex” - I’ll expand on this concept in a later post).

Generalizing and abstracting as necessary, while adapting our wording to the target audience.

Structuring outlines that best fit the intended messages of the product.

Iterating on drafts while prioritizing aspects of most importance (otherwise we might find ourselves iterating indefinitely in search of perfection, and thus missing the opportunity to make an impact - avoiding this requires bravery of sorts, in order to choose our battles and know when to stop).

How to Get There

Research must be treated as a discipline, meaning that we can learn and improve by studying theory, imitating the work of others, and cultivating our experience; there is room for trial and error, and therefore reflection; and we must adapt our methods to different domains and refine our toolkit as new technologies emerge.

However, research can also be treated as an art form, meaning that there are different ways to achieve the same goal; intuition develops over time and plays an important role in our decision-making; and the craft requires a certain headspace or state of mind.

Taking this into consideration, I think the tl;dr of achieving research fluency is picking up the following habits (I’ll elaborate on each of these in turn).

Prepare

Submerge

Flow

Practice

1. Prepare

This means equipping yourself by having a vast knowledge-base on hand, including previous related works (your own and those of others). This is meant to best support “flow”, by allowing the fluent researcher to continuously (bordering on obsessively) cross-reference via this knowledge-base, curate it (as described above) and utilize it for re-orientation (i.e. familiarizing ourselves with our requirements, sources, etc.).

Additionally, preparation refers to planning - but only as much as necessary. For long-term research projects, we should begin by clarifying our goals, mapping relevant sources of information and past research products (to be used either as references or exemplars) and identifying subject-matter experts we should consult with.

2. Submerge

Basically, submerging means starting quickly and boldly, by reflexively looking up information as soon as we have the slightest idea what to search for, and by drafting as early as possible (in terms of content as well as design).

The fluent researcher confidently gets to work almost immediately, and just tries doing look-ups for whatever; asking around to utilize the expertise of peers; and putting something (anything!) on paper, without fear of making a mess (and messes will surely be made).

Submerging entails adopting a (conservative) “fail fast” mentality, by testing ideas in the field, quickly getting feedback and continuously iterating. To paraphrase Cunningham’s Law, the simplest way to get the conversation and iteration process going is to take initiative and just start writing.

However, the fluent researcher retains responsibility and ownership over their product, and never sends a draft to review without meticulous proofreading and marking specific sections and issues for consultation during the review process.

3. Flow

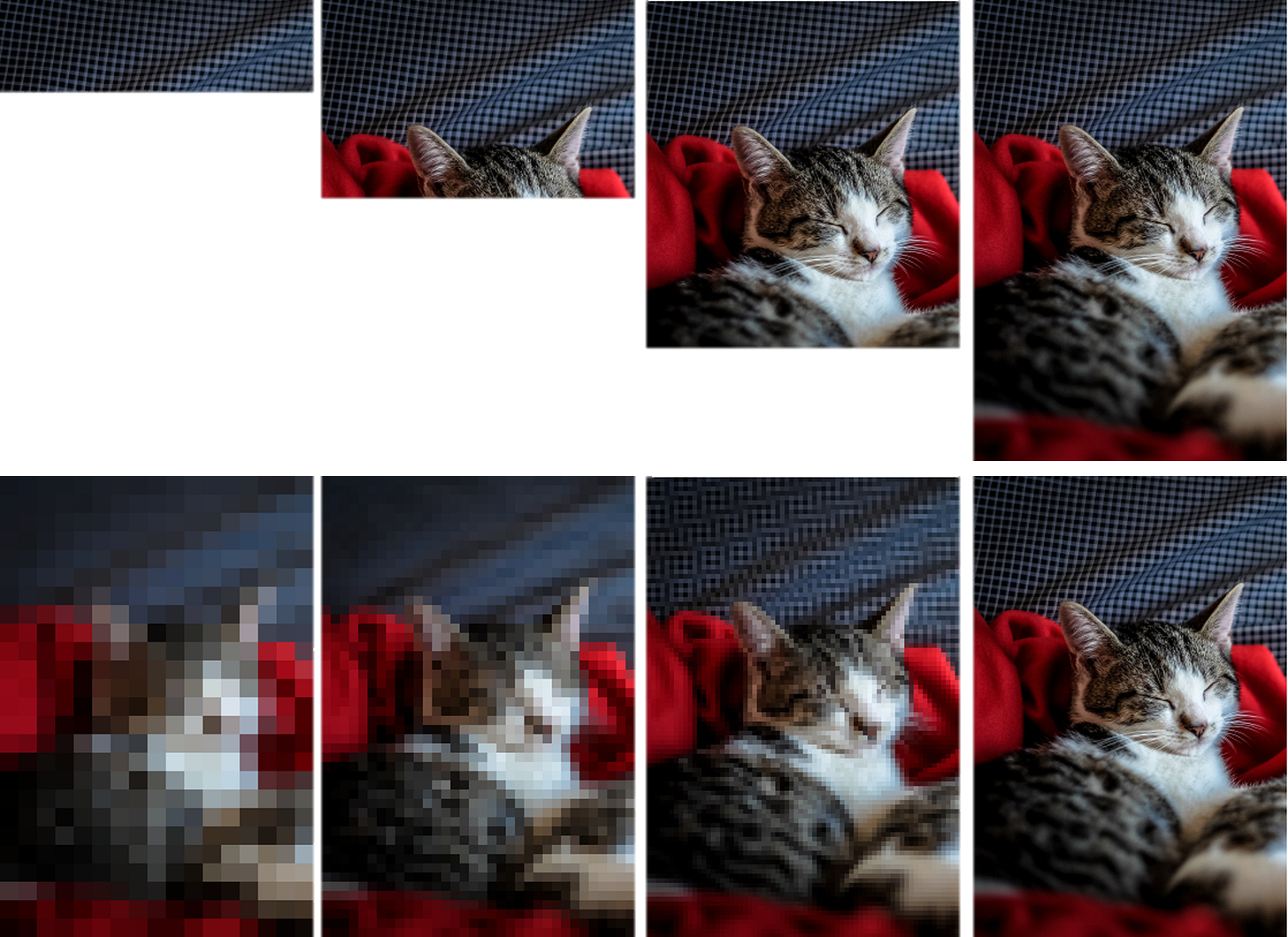

The fluent researcher works progressively, so that each draft iteration can serve as a relatively useful product on its own. An analogy for this style of work can be found in the progressive JPEG compression format, wherein the image is completely visible albeit blurred during the entire loading process (as opposed to baseline format, wherein the image remains partially obscured throughout):

We can point to another analogy in the intermediate levels of organ complexity observed throughout evolution by natural selection, à la ”The Blind Watchmaker”:

Practically speaking, this means quickly documenting our findings by gisting the material and moving on to the next item of data; continuously drafting on all “layers” of the product in parallel (reference, fact, assessment and conjecture); and of course, curating our knowledge-base as we go.

To flow is to keep pulling threads, by “pushing through” the raw material, imagining or visualizing what we’re looking for and pivoting accordingly, and cross-referencing and re-orienting via our knowledge-base (as explained above). It also means having a solid research plan but valiantly revising it as we learn new things, and iterating on our product outline as necessary.

As we flow, our attention should be focused on solving important puzzles, by evaluating novelty and recognizing and dealing with contradictions (between various items within the material, or between the material and our current assessment). In other words, the fluent researcher is attuned to novelty and contradiction, and devotes much of their time and energy to resolving contradictory discoveries.

While examining raw material, we must strive to collect useful and valuable information, such as information that can lead us to more information (via pivoting); information we can use as evidence to support an argument (this usually translates to references in footnotes); or information that might prove useful only at a later point in our research (to support analysis of competing hypotheses).

4. Practice

The fluent researcher is constantly iterating (as made clear above), and spends time rereading and utilizing their own past works and discourse in order to cultivate their experience.

They also spend a great deal of time interacting with their peers, by reading others’ work critically and sharing their thoughts with them; exposing their own work to critique, feedback and ideas; taking part in discourse, finding something distinct to say and making their voice heard; showing (off) their work early, while sharing raw findings and initial insights (but clearly indicating them as such in order to avoid confusion).

As we practice research as a discipline, we should periodically go meta, by thinking about research professionally and methodically; reflecting on our work and learning from past triumphs and mistakes - these should be developed into checklists, to be used during proofreading, for example.

Common Research Mistakes

Parroting technical terms (one should never use a word without understanding its meaning, at least abstractly).

Straying (too far, or without justification) from the local conventional style and wording.

Mixing “layers” (reference, fact, assessment and conjecture).

Mixing chronological vs. logical sequence (i.e. hopping between different types of story-telling within the same tale).

Misrepresenting evidence.

Misusing probability (likelihood) and confidence descriptors, or avoiding them entirely.

Working too linearly (as opposed to exploring diverse avenues in parallel).

Analyzing in a vacuum:

Ignoring biases (the Streetlight effect)

Missing (or ignoring) the state-of-the-art:

Not “conversing” with the reigning paradigm.

Not referencing earlier work.

Not utilizing personal or organizational experience in other domains.

Closing Thoughts

In conclusion, to attain research fluency, we should work on acquiring the habits mentioned above (prepare, submerge, flow, and practice).

This takes time and effort, but there are also unique advantages to being inexperienced (generally speaking or in a specific domain): a novice has the privilege of a fresh perspective; it can be easier to spot new types of patterns; they are less constrained to reigning paradigms; they have less emotional baggage related to past failures; and they are more open to doing things differently (as well as giving failed methods another chance). Beginners should (cautiously) make the most of these traits while they last, for fluency is sometimes accompanied by a certain rigidity of thought…