TL;DR:

Research products are made up of “layers”, namely:

Assertion (what are you saying?)

Evidence (how do you know?)

Citation (how do you know what you know?)

You should clearly differentiate between the various layers throughout your entire product, so that your readers can distinguish fact from conjecture or assumption.

It’s important that you qualify your statements with confidence and probability descriptors.

There is a lot to say about writing good research products, and I intend to eventually cover this topic in greater detail, including a discussion on the basic building blocks of a research-oriented paragraph and how to construct one effectively according to a general blueprint. However, today I’ll focus on a more narrow and elementary subject: the informational “layers” of a paragraph.

Every research product, long or short, is made up of paragraphs, which are usually organized into sections, chapters, etc. Each paragraph in a research product plays a very particular role, which is to convey a specific assertion to the reader. This might be about the existence of some phenomenon (“Jupiter has the largest anticyclonic storm in the Solar System”) or about a connection between multiple phenomena, such as correlation (“Taller people are usually heavier”), causation (“Smoking increases the risk of developing lung cancer”) or lack thereof.

Cohesive and well-structured paragraphs usually contain only one assertion, but sometimes it’s best to take a single large or bold assertion (e.g., “Bright clothing is a liability during a stealth mission”) and break it down into a “chain” of smaller assertions while adding explanations as necessary (“Bright colors are easier for most people to make out against a dark background, so wearing bright clothing at night could cause us to be seen by the enemy, which would be detrimental to the success of a stealth mission”). The level of detail here depends on how knowledgeable we expect our audience to be concerning the subject matter of the product.

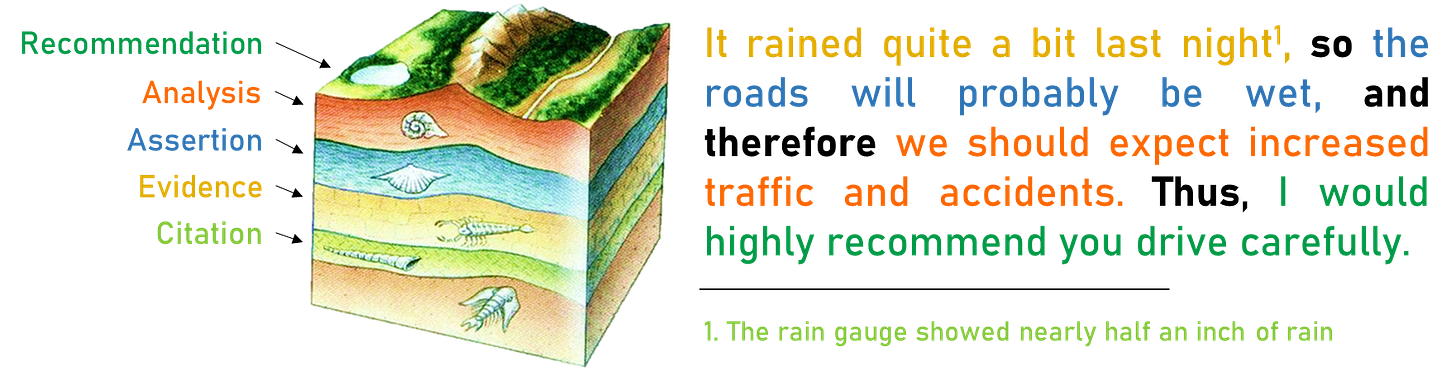

An unfounded assertion is easily toppled, so the topmost assertion layer is supported by a middle layer of evidence / facts, which is supported in turn by a bottom layer of citations (usually residing in footnotes, hyperlinks or parenthesized references). Essentially, each layer holds the answers to the following questions, separated by conjunctions (e.g., “and”, “but”, “therefore”):

Assertion / Claim / Conjecture — What are you saying? What is your point?

Evidence / Data / Facts — Why do you say so? How do you know?

Citation — How do you know what you know? (and how can someone independently verify this?)

Note that evidence could either be primary (as in raw material, such as an interview we conducted, a manuscript we analyzed or the results of some experiment we performed) or secondary (an existing prior work, such as an article or book).

While the above composition is a good fit for most paragraphs you’ll encounter in the wild, there are some notable exceptions, such as a Conclusions section, which brings forth previous assertions as evidence and presents a higher-level analysis / thesis as an assertion (it would be improper to include a citation layer in this section, as that would mean entail presenting new evidence that should have been included much earlier in the product). Likewise, a Recommendations section shows prior analysis as evidence, whereas the assertion contains a call to action.

Furthermore, some short-form products have the recommendation appear in the same paragraph as the assertion, taking up a fourth layer, and some very short-form products even have five-layer paragraphs, presenting the reader with citations, recommendations and everything else in between.

Regardless, it’s critical that the reader be able to easily distinguish between the various layers throughout the entire product, so that they can understand which statements are factual as opposed to those which are conjecture (and thus arguable to some degree) or assumptions (i.e., assertions explicilty unbacked by evidence). Additionally, statements should be qualified with confidence and probability descriptors, so that the reader knows how certain we are of the veracity of the facts we have gathered, and how well-founded we perceive our conclusions to be.

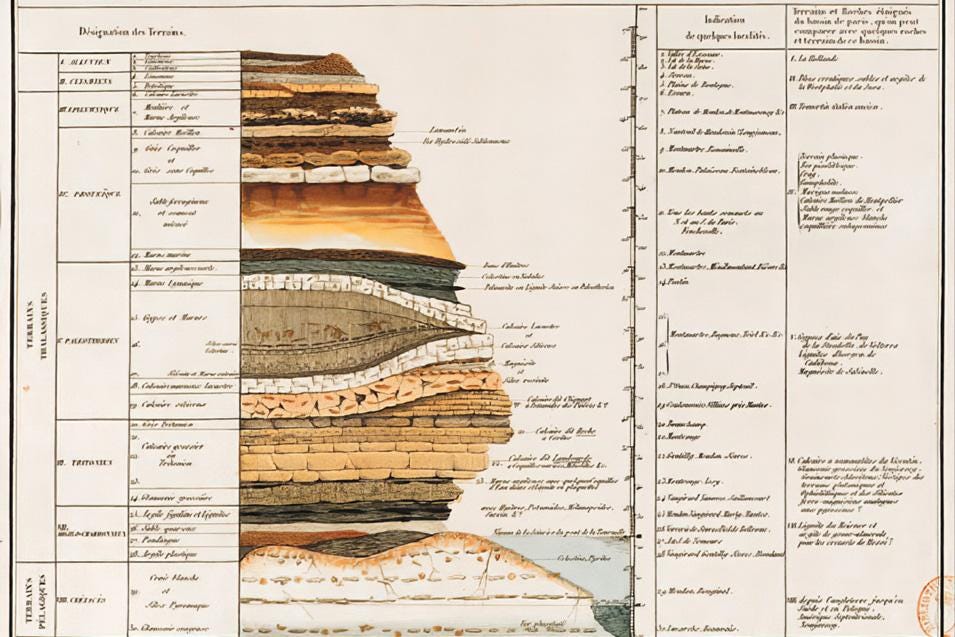

To summarize, here’s a color-coded stratigraphic diagram of a very simple research-oriented paragraph (one might even call this “stratiparagraphy”):