Research necessitates bravery, in the sense that the researcher must overcome their fears in order to succeed in their role. This post will discuss what makes a research product useful, examine how a product can be “too good for its own good”, and attempt to explain why bravery is therefore essential for research.

What Makes a Product Useful?

The utility of a research product can generally be said to depend upon it’s accuracy and consequentiality (i.e., it’s ability to affect reality). In academia for example, one might measure the latter quality in terms of an article’s citation impact.

In intelligence, a research product’s consequentiality hinges on its actionability. An actionable product must be able to convey the researcher’s estimations and recommendations to decision-makers on time, when they need to make a well-informed decision (whether they are waiting on the researcher’s insight or not).

There are several factors that determine a researcher’s ability to influence reality, including their technical ability to make clear, convincing and practical recommendations; their understanding of their organization’s culture; their ability to involve themselves in decision-making processes; as well as their personal reputation and that of the team with which they are associated.

Each of these subjects is deserving of its own post, but today I’d like to discuss two significant limiting factors which are in constant competition throughout a product’s lifetime:

Timeliness (i.e., releasing the product on time)

Analytic confidence (i.e., how certain we are of our results, and how easily we can rule out competing hypotheses)

The Tradeoff

The contest between these two factors can be exemplified as follows: the price we often pay for taking the time to construct a “perfect” research product is to lose the opportunity to influence reality by contributing to decision-making. If we take too long to gather more data to build our arguments or further articulate them, we run the risk of simply being too late — the decisions will have already been made without our involvement, and our product will therefore justifiably be deemed irrelevant.

Conversely, delivering an “undercooked” product might have disastrous effects if decision-makers choose to act on our premature assessments, or we might be ignored for lacking meaningful contribution to the discussion other than “fuzzy” and unfounded hypotheses.

Therefore, we must aim to find the right balance between relevance and rigor (for lack of a better term). As the window of opportunity begins to close for making a decision, the potential relevance of our product decreases, and while our knowledge may deepen as a function of our work, we will most likely begin to see diminishing returns on our investment as time goes by. Moreover, excessive time spent on one project is less time spent on another.

At a certain point in the course of producing a research product, perfect becomes the enemy of good, and it is no longer worthwhile to strive for rigor, or else we risk the following undesired outcomes:

Succumbing to inertia, by continuing to work without clearly defined objectives or parameters of success, or in pursuit of an unattainable goal.

Being overly-thorough, wherein our product suffers from “bloat” in the form of extraneous and irrelevant data.

Scope creep, which manifests in iteratively moving the goalposts of our product, adding more features and attempting to answer new (less relevant) questions, all the while straying from our original target.

In the long term, we can compensate for tight deadlines and improve our chances of maintaining relevancy by routinely building our sources and knowledge base in the right areas (or growing it in the right directions). Thus, by having a good starting point on hand in terms of both collection and analysis, we can answer research questions more easily and at a faster pace, resulting in products that are both timely and well-founded.

The trick is in choosing where to focus our attention at any given time, and in anticipating what questions we might be required to answer. Generally speaking, this can be achieved by identifying potential convergence points between our organization and reality. Moreover, we must make sure that at least some of our analysis and collection capacity is devoted to exploratory and future-facing efforts, regardless of whatever questions we are confronted with by decision-makers at present.

A Place for Bravery

It should be apparent at this point why bravery plays such an important role — when tasked with delivering an assessment or recommendation (particularly on a short schedule), researchers will almost assuredly encounter the following challenges:

There is no straightforward or trivial analytic solution to the problem (if such a thing existed, the research would be unnecessary), and we often lack for data (analysis nearly always involves extrapolation to a certain extent).

We must take ownership of our assessments, and if we successfully convince decision-makers to act on our advice, we will impact reality, for better or for worse.

These facets of research can be highly intimidating, as we may find ourselves doubting our own analytic and rhetorical capabilities; we might dread the possibility of being ignored and the fruits of our labor shown to be uninteresting or unconvincing; or of being proven wrong, our assessment turning out to be woefully incorrect.

Faced with these fears, it would therefore be tempting to prefer rigor over relevance. But bravery entails identifying the proper point at which to finalize our work, killing our darlings if necessary, and ultimately taking responsibility for the consequences of our product, whether our not it proves consequential.

Optimizing for Utility

The questions we must answer are therefore how to determine when to put down our pen and cease our efforts, where we should compromise and where we should not. This can be especially difficult if we’ve been working on something for so long that we’re no longer able to view it objectively.

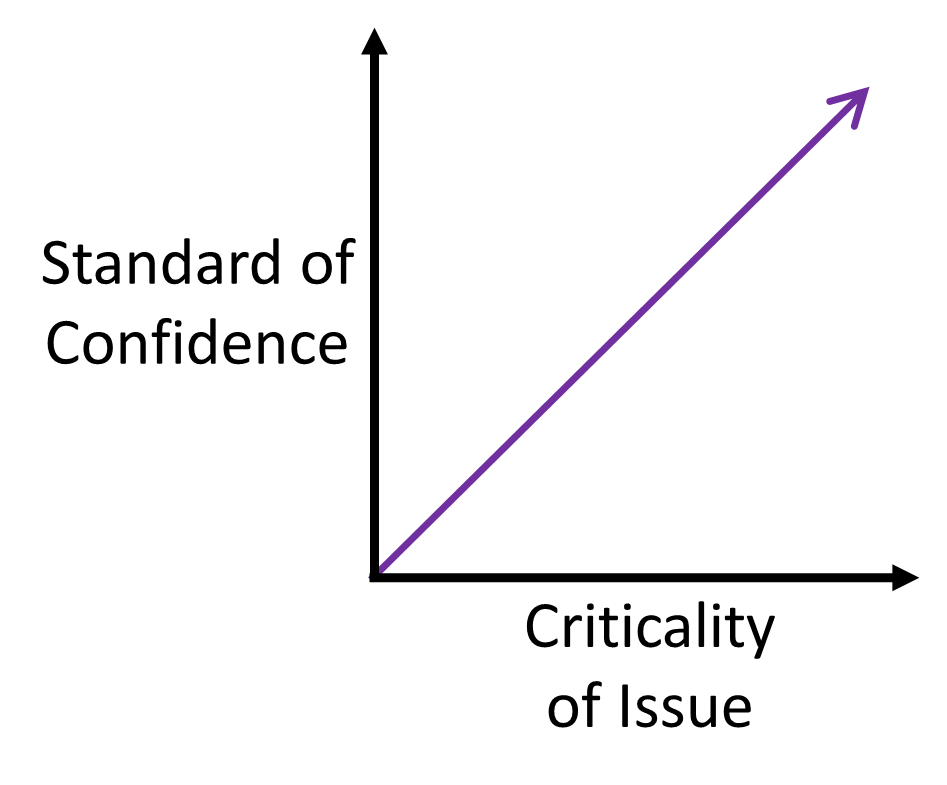

An important idea to keep in mind is the Pareto principle, which encourages us to maintain focus on the aspects of our work which are most impactful, while carefully compromising on the quality of others. In the context of intelligence research, this focus should manifest in working to improve the confidence levels (or foundations) of our assessments, whereas impact is equivalent to criticality. This parameter can be determined by our estimation of whether or not a given issue deals with phenomena in reality posing a significant danger or opportunity.

In other words, the standard we set for analytic confidence should correlate positively with the criticality of the issue at hand. To this end, we should learn to differentiate between issues of higher and lower criticality, and between assessments of higher and lower maturity (in terms of fulfilling their confidence potential).

We can use this concept as a sort of compass, to guide our collection and analysis efforts throughout the entire research process, and to help us make difficult decisions when push comes to shove — as our deadline fast approaches (whether external or self-imposed to avoid losing relevancy), by applying “differential treatment” to different parts of our product, we can make the following choice on how best to invest our remaining time (and thereby avoid bike-shedding):

The most critical parts of our product are the most deserving of further refinement (assuming they require it), in terms of both data (foundation) and clarity (phrasing).

Less-founded parts of the product which happen to deal with less critical issues should be preempted by low confidence descriptors, reduced in scope (and word count), or perhaps removed entirely.

The above principle should also be adhered to for another important reason: critical issues are generally more deserving of critical review, and we will often need to work harder than usual to convince both our peers and decision-makers of the veracity of our conclusions regarding them (especially if our results contradict commonly held views on the subject).

Like most things, our estimation of criticality becomes more accurate as we accrue research experience and gain a better handle on the bigger picture, but we can compensate for lack of experience by relying on the advice of our peers. Additionally, our research team’s collective ability to determine criticality can be honed by self-investigating the successes and failures of past products.

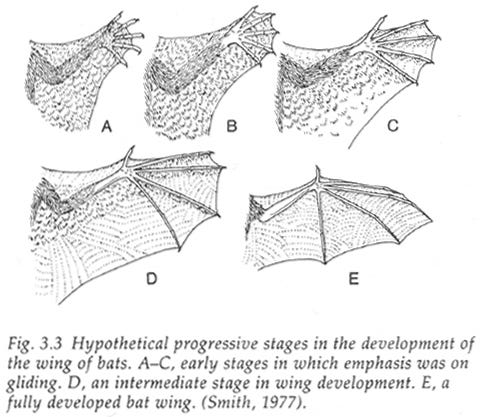

Beyond sustaining focus on critical issues, we can further optimize for utility by working progressively, and thus ensuring continuous capability to rapidly deliver a serviceable product if the need arises, one that is at least somewhat actionable (much like the wings of bats served various purposes throughout their evolution, initially allowing gliding and eventually enabling true flight). This style of work has the added benefit of allowing us to maintain an accurate “snapshot” of our progress throughout the entire lifetime of the product, which can make it easier to expose ourselves to the criticism of our peers (itself an act requiring a great deal of bravery).

A Coda on Failure

If our research product ends up being inconsequential or our recommendations have negative consequences, try to remember that every product (and process) has room for improvement, and research is a long-term endeavor. We should therefore seek, create and seize opportunities to learn from our mistakes (both analytical and operational), by understanding what went wrong and how we can avoid such errors in the future. Additionally, it is vital that we admit to our mistakes and correct them (tapping into our bravery once more).